Continuity and Transition in Russian Literature Abroad

Бог сохраняет всё; особенно – слова

Прощенья и любви, как собственный свой голос.

Joseph Brodsky wrote this poem on the centenary of the birth of Anna

Akhmatova. In this poem, Brodsky tries to convey what the Russian

philosopher N. Berdyaev meant many years ago when he said that to

understand Russian culture, one must first of all keep in mind the

religious nature of Russian ideology. Here, the basis of morality is

the Christian ideal of spiritual life which is represented not by a

physical person, but by a spiritual face. The spiritual faces of

Russian saints are depicted in numerous icons painted by Natasha, but

many more are depicted on her icon-painted eggs made in the style of

the great Russian master Karl Fabergé.

Natasha inherited her love for icon painting from her grandmother who worked in one of Karl Fabergé’s workshops in St. Petersburg at the beginning of the twentieth century. In her childhood, instead of toys, her grandmother allowed Natasha to play with real porcelain eggs made at the Karl Fabergé company in St. Petersburg. Although the imperial Fabergé eggs are better known, many of the eggs created in Karl Fabergé’s workshops depicted Russian saints. Thus, the spiritual component of the eggs, their religious background, penetrated and remained in the child’s soul forever.

Much later, as an adult studying religious drawings and paintings by old masters at art school in Moscow, Natasha managed to create her own unique artistic style of icon painting on wooden eggs using the miniature painting technique. At the same time, the religious component gradually began to occupy a significant place in Natasha’s worldview which was inevitably reflected not only in her poetry but also in her short stories (Late Awakening, Temple at the Hospital) and in her painted eggs where she portrayed saints and biblical scenes.

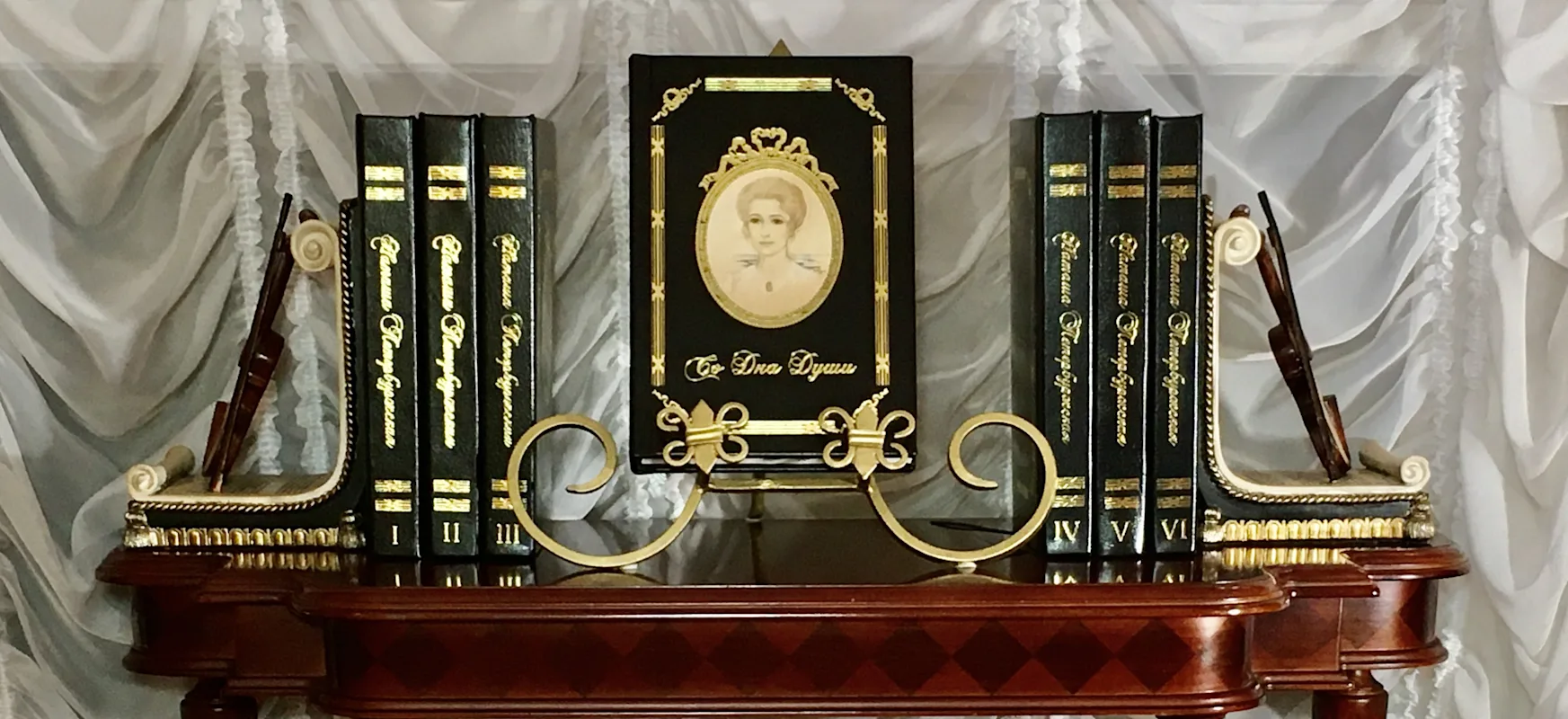

Natasha’s productivity only increased with time, as exhibitions of her paintings were organized, her new poems and short stories were read by members of the Society of Russian Literature in California, and more of her books were published. In 2022, Natasha’s first book of poems written only in the United States (her first and second books of poetry having been written mostly in the U.S.S.R.) and her first volume of short stories written partly in Moscow and partly in the U.S. were published. In 2023, two new volumes of short stories were published, and more volumes were planned.

Приходит сон и с ним ложатся строчки,

И расплывается кругами бытие,

И засыпаю я без проволочки,

И вот уже плыву в серебряной ладье,

И звёзды, задевая край бортов

Мне освещают тайны суть,

Хранители моих прекрасных снов

Показывают мне дальнейший путь.

Вот небо светлое и лестницы видение,

Осталось несколько ступенек,

Два Ангела стоят, как привидение,

У врат знакомый мне священник.

Прижизненных не нужно будет дач,

Ни арлекинов выездных, ни карнавалов,

Других решать придётся там задач,

Там девять замкнутых кругов до перевала…

Меня здесь больше нет,

Нет больше мыслей в лицах,

На всё есть в Библии ответ,

Ищите нужные страницы.

Проходит жизнь без созерцания,

Пустое время, тополиный пух,

И дождь не слышит понимания,

Он льёт не про себя, а вслух.

Лень в людях торжествует

И лозунги со всех колоколов,

И ложь, и брань невидимых врагов,

Народ за всё проголосует.

Где вера, где надежда, что сегодня?

Где просветлённые уверенные лица?

Ищите в Библии господней,

Ответы в каждой есть странице.

The unbroken connection between Russian poetry of the twentieth century, the Renaissance in the Silver Age of poetry in Russia, and the great Russian literature diaspora from the middle of the twentieth century up to the end of that century is embodied in the poetry of Joseph Brodsky, and is best expressed in his Nobel speech:

The fact that not everything was interrupted, at least not in Russia, can be credited in to small degree to my generation, and I am no less proud of belonging to it than I am of standing here today.

But this connection has not been broken even today, following Brodsky’s death in 1996. In the first half of the twenty-first century, the work of Natasha Petersburgskaya continues the centuries-old traditions of Russian literature, expressing truly Christian values, and stretching a connecting thread from Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva to our present day:

Dedicated to Anna Akhmatova.

Бог сохраняет всё

Отпевали в Никольском соборе,

Последний колокол тревожно отзвенел,

В сердцах печаль, отчаянье и горе,

Народ навеки овдовел.

Как говорят, церковные законы,

На отпевании зажжённые лампады,

Что вклады умершей определённо,

Внесли в наш мир огней каскады.

Паникадило освещало грустный путь,

Так завершилась жизнь её земная,

Висела скорбь, никто не мог вздохнуть,

С иконы Чудотворца слеза стекла сухая.

Она вошла с ветрами лёгкими

В поэзию Серебряного Века

И в жизнь – трагедию с годами горькими,

И в жуткий мрак длиной в полвека.

Испив всю горечь унижений

И потеряв всех сердцу дорогих,

Наследие передала нам без сомнений,

Влияние праведников и святых.

Прощались мартовские холода, ветра сухие,

Ушла последняя звезда Серебряного Века,

Неискуплённая вина лежала на России,

Ахматова – бессмертие до будущего Века.

Dedicated to Marina Tsvetaeva.

Я одна осталась вами не понятой,

В этом мире газетных людей,

Вы, с закрытыми ладонями,

Стадо зависти злых нелюдей.

Что осталось нам в жизни прожитой,

После Бродского и Мандельштама,

Вам Марина, ненавистью обвитой,

В лампе зелёной была нежданна.

Не дано Цветаеву вам узнать другую,

Нервущуюся к Гумилеву в цех,

В собранье лжи, в немыслимую сую,

Автографом своим пересечёт вас всех.

Испытывая ужас и благоговение,

Живёт средь вас живая совесть,

Как столкновение,

И чар её и беспредельна её горесть.

To this day, there is no clear answer to the question of whether there was a fourth wave of the Russian diaspora from 1990 to 2010. In the future, researchers will be able to describe this movement in more detail, but for now it is certain that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, people rushed to save their families from the brutal rampant crime of the 1990s, and an incredibly large number of the most diverse layers of Russian society emigrated abroad. There were no famous personalities among them, such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky; these were simpler people, with less ambition, but creative and vulnerable. And they, just like the representatives of the first wave of the Russian diaspora at the beginning of the twentieth century, carried kindness, compassion, and mercy in their souls.

Mercy, in the minds of representatives of Russian culture, is connected, on the one hand, with religion and spirituality, and on the other hand, with the soul, salvation, humility, faith, forgiveness and goodness. The soul, as it is known, is the leading concept of Russian mentality and is perceived in unity with spirit and body. The spiritual significance of the soul in Russian culture is undeniable and is determined, first of all, by the divine origin of the soul and its immortality, in contrast to the mortal and fragile human body.

Love, Natasha’s main character trait, is manifested in empathy and a sincere desire to help people in trouble who are suffering and in need of support. Both in Moscow and in San Diego, this trait has been reflected in her work. All of Natasha’s short stories are imbued with love. Like the Russian emigrants of the first wave (Ivan Bunin), Natasha, with her creativity, brought kindness, compassion, and hope to the world because this is precisely the meaning of human life.

Love, in Christian teaching, is defined as the greatest value in the world. The Christian upbringing that Natasha received as a child, from her grandmother, is expressed both in her work and in her life. Caring for the well-being of another person is possible only if a person has love in their soul. From the first poem written to the last published short story, Natasha’s work is permeated with love, the spiritual ideal of which is always preferable to pragmatic values. It is safe to say that the formation of such an ethical constant began in Natasha’s early childhood and has continued throughout her life.

In his Nobel speech, Joseph Brodsky stated that:

Regardless of whether one is a writer or a reader, one’s task consists first of all in mastering a life that is one’s own, not imposed or prescribed from without, no matter how noble its appearance may be.

In her life, Natasha’s desire is to convey to people, through her creativity, the great foundation of Christianity—love—as a necessary basis of human existence, not only in consciousness and philosophy, but also in the creations of Natasha Petersburgskaya.

Не красота наш мир спасёт,

Любовь спасёт и послушание,

Душа найдёт покой, и сострадание,

И веру в Бога обретёт.