In 1964, Natasha left the damp, but great, Leningrad behind. Her first poems and paintings were being kept under wraps, waiting for a better time to be published and exhibited. The short Thaw, which never turned into spring, had ended. The government had imprisoned Joseph Brodsky and closed the Leningrad literary meeting clubs. There was nowhere else to meet and talk about poetry and creativity, to read and exchange opinions about what one read in samizdat. The country was returning to its roots, and it was necessary to live somehow. Compared with this stalled and stifling situation in Leningrad, the Art School in Moscow looked unusually attractive, and even though it was impossible to enroll in the Art Department, the Decorative Arts Department seemed very modern. In addition, everything was very inspiring and tempting: the city of Moscow, new people, new acquaintances, and new studies.

Москва! - Какой огромный

Странноприимный дом!

Всяк на Руси – бездомный.

Мы все к тебе придём.

Having previously resided in a separate apartment with her father and grandmother in the center of Leningrad, Natasha now lived on the outskirts of Moscow in a tiny room in a communal apartment with 36 neighbors. This life was new, but it was fun and friendly, and everyone was mutually helpful. New poems appeared:

И опять нам кто-то обещает

Уберечь от страха и забот,

И опять твоя душа прощает

Промелькнувший, обманувший год.

Studying at an art school was not difficult, and after meeting the famous Soviet artist Nina Alekseevna Sergeeva, who became her mentor as an easel painter and for whom Natasha sat as a model, a completely new life began with the blossoming of the Moscow spring. And again, new verses:

В изумрудной лазури гуляла,

Опуская следы в песок

И душа её тосковала,

Вдыхая морской ветерок.

Вспоминала лиловый закат

И запах холодной лаванды,

Пролетел и вернулся назад

Горький шёпот осенней баллады.

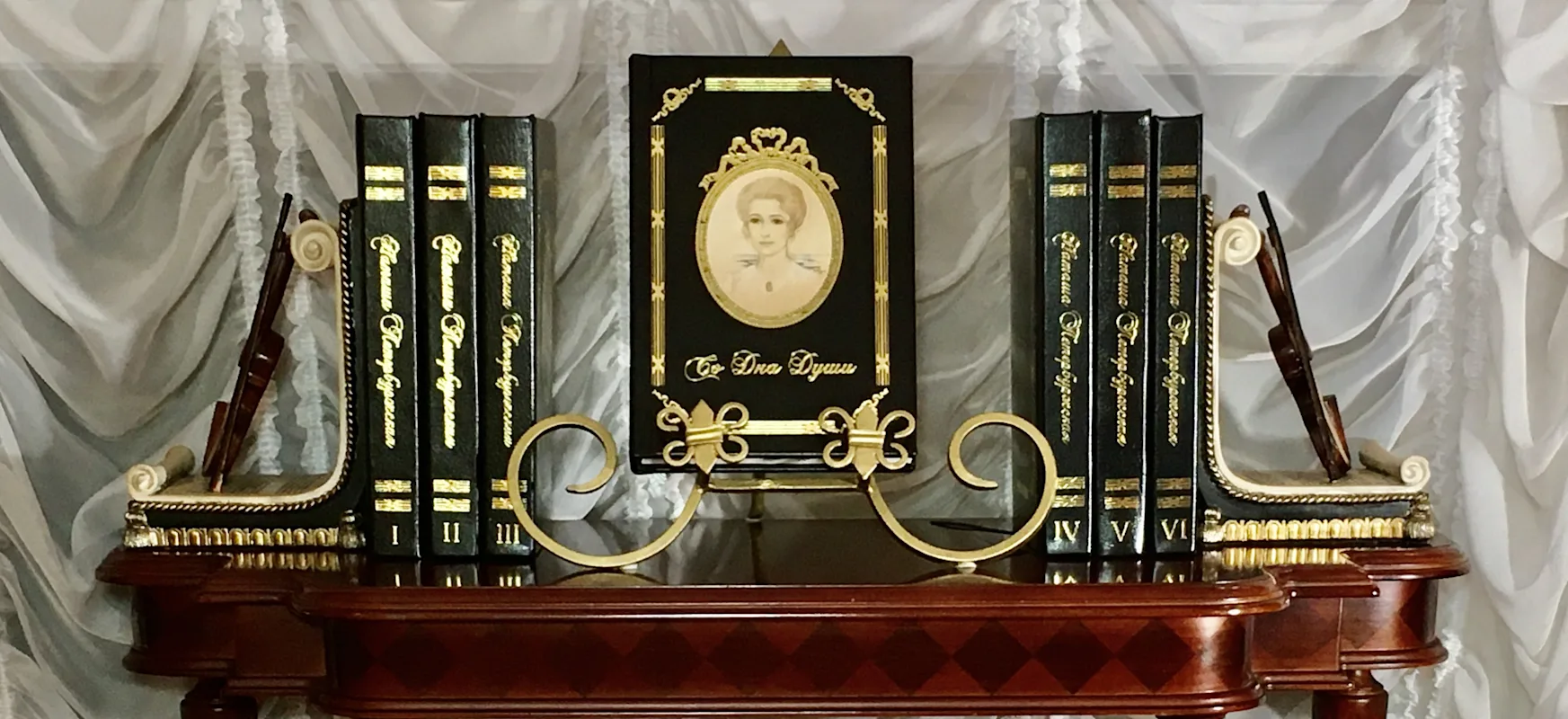

Then a wonderful opportunity appeared. The Soviet government offered an apartment building (a cooperative) for sale in the center of Moscow on Chekhov Street. It was named “Youth Theater” and was for sale only to young artists. This famous place provided the opportunity to communicate with artistic, theatrical, literary, and of course poetic creativity in new meetings and with new acquaintances. This creative stage lasted for almost ten years. During this time, Natasha wrote many soulful and touching poems, as well as several new short story collections (Moscow, Castanets, Anatoly). Visiting and invited guests listened with pleasure and praised, but again, nothing changed. The lack of membership in the Writers' Union meant there was no opportunity to be published in Soviet newspapers and magazines.

Лежат стихи под пыльным пианино,

В них шёпот обещаний кем-то давших,

В них жизнь незримая проплыла,

Как лепестки цветов опавших.

Мои стихи о нежности и смерти

Лежат теперь у плинтуса в тиши.

Когда писала их, поверьте,

Как с болью вырывались из души.

Романсом им не стать печальным,

Я в памяти их трепетно держу

И пусть не их удел сакральный,

Но я смахну скатившую слезу.

И вспомню давний, грустный вечер,

Как он ушёл, задув свечу.

Нет, время никого не лечит,

Но я об этом лучше промолчу.

In the U.S.S.R. the 1970s was a time of so-called stagnation, but also of active opposition to Soviet power by the creative intelligentsia. A movement was emerging that would be called “Dissidence” in which many famous figures of science and art increasingly spoke out against the Communist Party. Persecution of the intelligentsia began, and Joseph Brodsky, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Sergey Davlatov, and Andrey Tarkovsky were expelled from the country. The Taganka Theater, which at that time was a national center of artistic independence led by the theater’s chief director Yury Lyubimov and the nationally-famous bard Vladimir Vysotsky, was closed. Yury Lyubimov escaped from the country and Vladimir Vysotsky died—his heart could not withstand the colossal stress. The world-famous musician Mstislav Rostropovich left the country, and the world-famous scientist and academician Andrey Sakharov remained unemployed. And these are only the most famous personalities! Add to this the thousands of ordinary people who, unknown to anyone, left the country. The fight against power required strength and enormous courage, and not everyone had it. For many, family and children were more important than political debates and the fight against power. Natasha continued to write poetry, including children's poetry (Chizhik, Fair), and read it to all her friends and acquaintances in her small literary and artistic salon on Chekhov Street in Moscow. During this time, Natasha also married and had a daughter. And again, new poems appeared:

Хочу вернуть вчерашний день,

Ручей и летнюю прохладу,

А вижу на веранде тень,

Да сломанную, старую ограду.

Смотрю на сад, в нём спит печаль,

На яблоню, давно пустая

И возвращая мысли вдаль,

Стоит она, как молодая.

Уверенность в бессмертии души,

Освобождение от страха смерти,

Жизнь не гневи и не греши,

И Бог вернет вчерашний день, поверьте.

Белые на синем плыли корабли,

Тихо вспоминали молодость, Шабли,

А теперь кораблики на другой волне,

Память возвращая изредка ко мне.

Там была любовь, прощание и грусть,

Там была нирвана и слёзное вернусь,

Там глаза светились, сапфирами горя,

Не желая верить в расставания.

И мерцая волны уносили в даль,

Вспоминая время-не унять печаль…

In 1985, Perestroika began. It was a period of political reorganization of the Soviet Union when it was thought that everything old would go away, and everything new and supposedly better would immediately arrive. But despite this belief, a huge flow of scientists, intellectuals, artists, and ordinary people sought to leave the country. No one understood that in a few years there would be a complete collapse of the entire system, and that the entire Soviet Union, including millions of highly educated and highly qualified specialists, would find themselves unemployed on the streets without any means of subsistence. They worked as taxi drivers, garbage collectors, and janitors in order to feed their children. The tragedy overtook the entire country, and evil spirits rose to the surface and seized many key positions in the country. But the small literary and artistic salon on Chekhov Street did not disappear. For a long time, it attracted many lovers of Russian literature and art due to an endless, organic manifestation of kindness characterized by: a desire and willingness to share warmth with others, mercy, a recognition of the right to make mistakes, the ability to forgive and help, and the desire to do something pleasant and useful for each person. One of Natasha’s most cherished moral qualities—to promote the happiness and well-being of others—attracted, like a magnet, a variety of people to this small, intimate, literary and artistic salon.

Вот и снова зима,

Белым снегом покрыло дорогу

И поспела хурма,

И душистая ёлка прижалась к порогу.

Скоро будет стоять, как всегда у камина,

Словно фея лесная в серебристой фате,

Запах детства из хвои и мандарина,

Колдовать в новогодней со мной суете.

Будут свечи гореть и шампанское пеной,

И желания жечь под рубиновый бой,

Хоть волшебное платье из кружев надену,

Всё равно, мой любимый уедет домой.

In the early 1990s, Natasha’s husband received an unexpected invitation to work in the United States, and the family left the collapsing Soviet Union and moved to the New World.

Shortly after moving to the United States, Natasha organized a Russian poetry club in her rented apartment in San Diego, California, where lovers of Silver Age poetry gathered together and read and discussed poems by Akhmatova, Mandelstam, and Pasternak. Natasha also read her old and new poems and short stories. Later, this club changed its address, and for many years was located in an art gallery in downtown La Jolla. In 2007, the Society of Russian Literature in California created its first website, poetrypoems.net so that everyone could appreciate great Russian culture, poetry and literature. Power changes, but culture is eternal.У любви нет последней страницы,

У любви есть надежда всегда,

Не стирай, между нами, границы,

Всё прошедшее, только вода.

Позабудь про любые невзгоды,

Про ошибки свои позабудь,

Ведь у нас впереди ещё годы,

Где любовь, понимание, суть.

Нарисуй мне на мокром песке

Своё сердце и нежное слово,

Чтоб не жить в постоянной тоске,

Чтобы снова к любви быть готовой.