In the dark post-war years, when the Thaw was still far away, fragments of the Silver Age—a wonderful and completely unreal era of creativity and love—were destroyed by the revolution, in the flames of which many future geniuses burned. Nevertheless, the Silver Age continued to excite the souls of creative youth. Already, other artists and poets shone on the banks of the Neva, as a paraphrase from A. S. Pushkin’s famous poem “Eugene Onegin”. They were looking for freedom, sowing the eternal, hoping for a thaw, but in return, they received hopelessness.

The lives of Soviet people in those years were completely different from today. They were divided into poor and very poor, talented and very talented. They were helped by mutual assistance and were brought together by poetry, prose, and painting. Everyone lived on the same plane, looking at life through a magnifying glass, arguing, but trying not to lose each other. The atmosphere of protest united various artists and poets. This poetic life was based on ideals independent of Soviet ideology. In the context of that era, it is generally important to recognize this phenomenon: while, in the United States of America, thousands of people gathered to listen to rock music; in the Soviet Union, thousands gathered to listen to poetry. This sharing of poetry took place surreptitiously, and some of these poets even managed to unite into groups, although not for long.

One of these groups was formed in Leningrad around Joseph Brodsky, and the other took shape in Moscow around Leonid Gubanov. In these groups, poets and artists held lively, frank conversations about literature, painting, and poetry. In memory of Russian poets who had emigrated to France, they read poems by Vladislav Khodasevich and Andrey Bely. These poets and artists believed that goodness has the power to transform both individuals and society; that it can bridge differences and promote cooperation and unity; that kindness not only makes life more enjoyable and happier but can also be the key to solving the global problems that a person encounters. In the souls of each of these educated, talented individuals, despite the terrible times, hope flourished. But in the end, their souls burned out. Soon Joseph Brodsky was convicted of parasitism, sent into exile, and then forcibly expelled from the country—which ultimately saved his life. Leonid Gubanov underwent compulsory treatment at a psychiatric hospital where he died in almost complete obscurity at the age of 37. The theme of innocent sacrifice and the poet’s fatal doom in a hostile world was characteristic of many poets of that time:

А кто вложил вчера в сирень

Букет из чёрных роз,

Цветы, цветы, пора, уж день

Нет, нет, немного грёз.

И ты пришла цветы смотреть,

Но что же так темно?

Я понял — это значит смерть,

Я это знал давно.

In those years, there were two ways to get published - samizdat (typewritten, handwritten or photocopied in the Soviet Union) and tamizdat (publication abroad and illegal distribution of manuscripts in the U.S.S.R.). With the end of the Thaw, these forms of existence of the new Russian-language literature became the only possibilities. Joseph Brodsky was published only in samizdat, but despite this, his poems were known throughout the Soviet Union. Boris Pasternak published Doctor Zhivago in tamizdat (abroad), and therefore, it was banned in the U.S.S.R. Nevertheless, it was illegally brought to the Soviet Union where it was in great demand among the intelligentsia of that time. It is noteworthy that both Boris Pasternak and Joseph Brodsky became Nobel Prize laureates in literature.

On March 13, 1964, at 22 Fontanka River Embankment in Leningrad, a meeting of the Dzerzhinsky People's Court took place. The building greeted visitors with the posted words: “The trial of the parasite Brodsky.” By an amazing coincidence, very close by, at 16 Fontanka River Embankment, was the house of His Own Imperial Majesty's Chancellery where, at one time both Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov were prosecuted. Joseph Brodsky personified, and lived as, a free person in a totalitarian, unfree society, and this both irritated and caused rejection among the monolithic mass of the worker-peasant system of the builders of Communism in the U.S.S.R.

In fact, it was not the refusal to work on the construction sites of the Soviet Five-Year Plans that brought about the persecution of Joseph Brodsky. The reason for everything turned out to be the human essence of the poet--his apolitical, but internal, aesthetic dissent. It is quite possible to apply the famous words by Alexander Griboyedov (“Woe from Wit”) to Joseph Brodsky during that time in Leningrad: I write as I live, freely and freely.

As reported by sculptor and artist Mikhail Shemyakin (“Mikhail Shemyakin about Joseph Brodsky”): Anna Akhmatova once said that there was the era of Pushkin. Probably, the time in which we live will be called the era of Brodsky.” A real persecution was unleashed against Joseph Brodsky. His innovative poetic language—radically different from the language of Soviet poets—and his independence were not just condemned; they were considered a crime and, therefore, prosecuted. Outsiders were not allowed into the courtroom, but endless crowds of people surrounded the building and did not leave until the very end. The full typewritten text of this trial was subsequently published in the West and serves as a vivid illustration of Brodsky’s contemporary era of the Communist-Party-ruled Soviet Union.

On June 4, 1972, after being deprived of Soviet citizenship, Joseph Brodsky flew from Leningrad, eventually making his way to the United States with the help of friends and supporters. Thus began a new, wonderful era in the life of the great poet.

Meanwhile, back in the Soviet Union, countless numbers of young and not so young boys and girls stood in line for hours in Leningrad just to hear Joseph Brodsky’s poems at least once at the infrequent secret meetings of poets. Brodsky’s poems were passed from hand to hand and read in a whisper because they were like a breath of fresh air in the stuffy atmosphere of Soviet totalitarianism. Many aspiring poets drew inspiration from his poems and tried to imitate him, although this was almost impossible.

Natasha, like many other young people of that time, eagerly absorbed these newfangled trends, went to poetry evenings, tried to write poetry, and listened, listened, listened to the whisper of the times. She began early to write poems about spring and about first love—touching, tender, naive. This was not literary creativity; it was an impulse of the soul. She didn’t read these poems to anyone because she was embarrassed. This trait, innate shyness, has accompanied her throughout her life. In addition to the challenges of lack of faith in herself and her talent, everything that was written had to be kept under wraps, waiting for a more opportune time for publication. In those days, the publication of poetry in the U.S.S.R. was possible only for members of the Writers Union. Of course, in order to earn a living, one had to adopt a profession and work. In order to write, one had to have the strength, perseverance, and fearlessness of a Joseph Brodsky, and not everyone had these.

The house in which Natasha lived in Leningrad at 2 Borodinskaya Street was a half-hour’s walk from 22 Fontanka River Embankment. Standing on the Fontanka embankment on a cold day in March 1964, waiting for the announcement of Brodsky’s verdict, Natasha realized that for any poet who did not glorify the Communist system, there was nothing to do in the U.S.S.R. The poet’s fate in the country was predetermined (prison or a psychiatric hospital); she resigned herself to this fact, but did not stop writing.

As a poet, she hid her emerging talent. She entered an art school in Moscow and became a decorative artist. This profession helped her to survive and to solve many everyday problems for a long time. But life knows how to present surprises, and one day fate smiled and gave her the opportunity to plunge into the world of poetry, where the sprouts of past literary creativity received a powerful boost that lasted for many years. Poems were written and paintings painted, but as before, no one needed all this wealth. It was still impossible to publish one’s poems, as well as to exhibit one’s paintings, without membership in either the Writers Union or the Artists Union.

And then life and fate took a new turn and brought the family to the United States of America, where the nascent buds of both poetry and painting finally bloomed. The Russian diaspora in Europe and in the United States offered an opportunity: an environment where authors unclaimed by Socialist Realism could finally publish their works—not only those written once upon a time in the Soviet Union, but also those that the authors had continued to write abroad. In some cases, such as those of Joseph Brodsky, Vasily Aksenov and Sergey Davlatov, notoriety in the U.S.S.R. helped arrange one’s life abroad. However, in those cases where this notoriety did not exist, life was not easy abroad either.

In this atmosphere, having surmounted countless obstacles, Natasha was able to succeed both as a writer and as an artist. In the early 2000s, she opened a modest literary and artistic salon in San Diego as a continuation of the long-standing Moscow chamber literary and artistic salon on Chekhov Street. In San Diego, as before in Moscow, everyone was invited to talk about poetry and read poetry, exchange opinions on books read, show one’s paintings, and organize art exhibitions of both new and old works. In other words, it was another place where artists of the Russian diaspora in the United States gathered. The group in San Diego, California was not as well-known as Sergey Davlatov’s in New York or Vladimir Maksimov’s in Paris; Natasha’s chamber salon was very private. Subsequently, she adopted the pseudonym Natasha Petersburgskaya (Наташа Петербужская) under which she published her poems and short stories in San Diego.

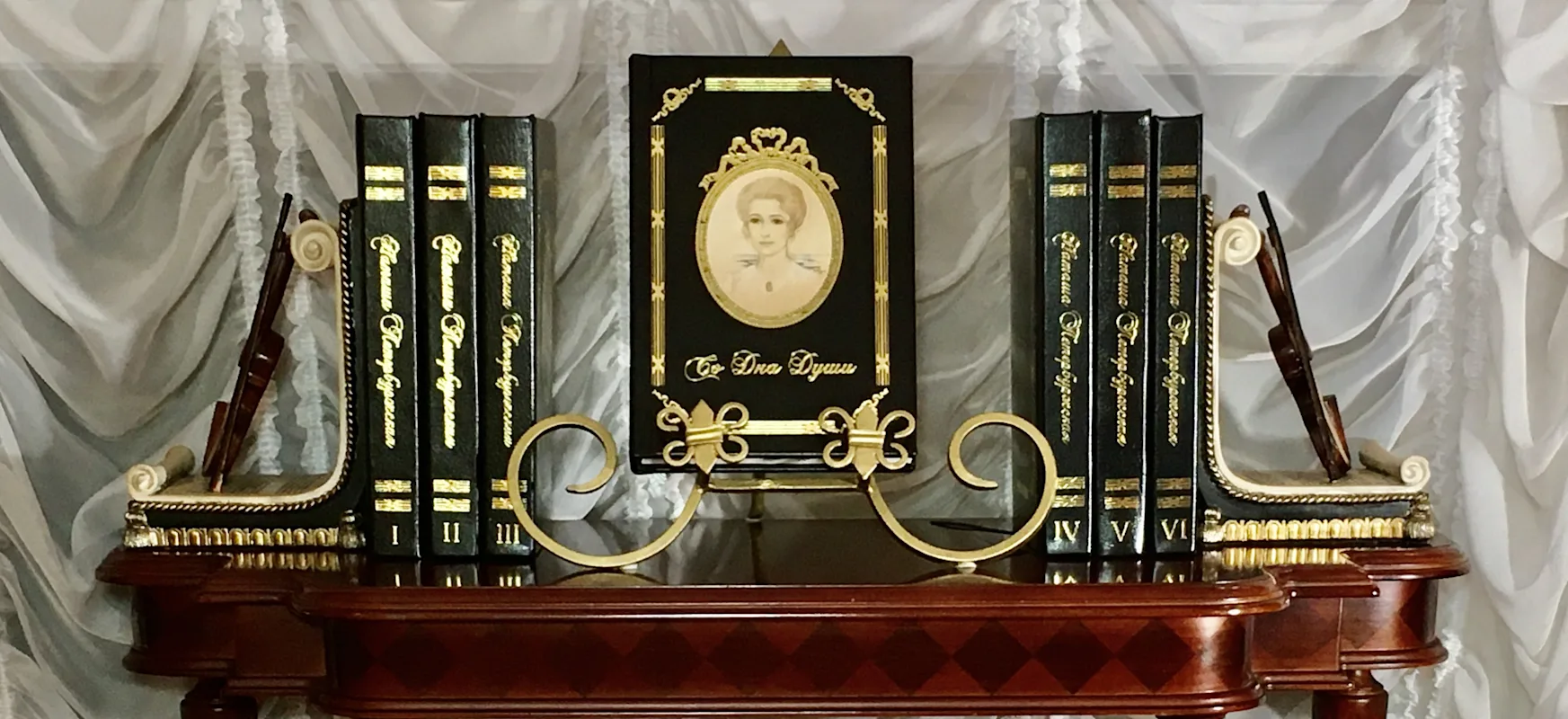

During this time, Natasha published, in Russian, three volumes of poetry and four short story collections, and painted several dozen oil and watercolor paintings. The first and second volumes of her poems were previous works written in Leningrad and Moscow that had never been published. Subsequent volumes of poetry and short story collections were written in the United States. Natasha has written all of her poems and short stories in Russian, unlike Joseph Brodsky, who wrote and published poems in the United States only in the Russian language, but wrote his essays and short stories only in English.